Valuing SaaS

The way that we look at valuations, specifically, the multiples that software companies trade at is disconnected from the reality of running a software business. We need a new way to look at Software-as-a-Service companies. The traditional methods of fundamental analysis don’t work. There’s a lot of information to digest here so I thought that I’d break it up into three smaller chunks so it’s easier to digest. I’ll be releasing the articles over the next few weeks.

This first part of this article introduces the general concepts. The second part talks about the three key line items for software businesses (General and Admin, Selling and Marketing, and Research and Development). The final section discusses the property analogue, works through an example, and looks at what a turning point (i.e. when you should sell) looks like when using this framework.

New-World vs Old-World

The accounting rules were created for companies that manufactured “things” (Old-World companies) and struggle to represent the underlying situation of companies that deal in bits and bytes (New-World companies). An HBR article touched on this back in 1996, there are increasing returns to scale in software businesses, which differs from how returns accrue to Old-World businesses. We need to take another look at how we’re assessing software companies to understand why a lack of earnings and correspondingly high earnings multiple might not necessarily be a bad thing.

The main problem is that if a software company has found a niche to exploit, we should encourage it to continue to do so. This requires more spending on what would typically be classified as “growth capital expenditure.” New-World businesses see this reflected in the income statement as increased costs in all the line items. Historically, this growth capital expenditure (capex) wouldn’t be reflected in the income statement - but would be reflected in the cash flow statement. This means that we need to be aware of what’s actually being built in the businesses. While code might appear ephemeral, the business that is built on top and around the code base is anything but.

To gain some understanding of how we can use traditional valuation methods to assess New-World companies, we can normalize the financial statements to give a more accurate comparison with Old-World companies.

However, an additional solution could be to look at the sales efficiency (defined below) to determine when New-World companies have matured. At this point, the accounting could begin to reflect the underlying realities sooner rather than later.

The Sample Set

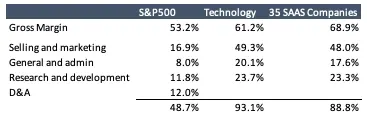

To exemplify this, I’ve pulled some data that is composed of three different but overlapping sets; namely: the S&P500, the Technology Industry (528 companies), and SAAS companies (34 handpicked SAAS companies that had the relevant data available) specifically. The numbers mentioned are averages of the past three financial years. While the sample isn’t exclusive (there are likely some other SAAS companies that haven’t been included), it gives a reasonably good illustration of the points that I wanted to touch on. I acknowledge that I could have spent longer cleaning the data but I just wanted to get a general idea of whether the ideas made sense.

Gross Margin

Starting at the top line, we’ll generally see relatively high gross margins (unit economics) for software companies. These gross margins could be 80-90% because the marginal cost of serving an additional customer is relatively small for some of the SAAS businesses. On average, SAAS company gross margins are 68.9%, while the S&P500 has 53.2% gross margins for comparison. This is something to be aware of when Old-World companies are trying to garner New-World valuation comparisons – Unless the gross margin is really high, it’s likely that the company is reliant on a number of widgets in a supply chain that it may have limited control over.

Having a high gross margin is important because it signals that the company has a lot of control over its own destiny (i.e. it isn’t using third parties for distribution). It also gives the company more margin to play with in the operations of the business. In the next article, we’ll look at what those operational expenses typically look like.

Breaking it down

When we’re looking at a software company, we could break out the key line items in the income statement and then work out where each of the ratios should realistically land in a steady state i.e. when the business has reached maturity. Generally, it’s misleading to look at the ratios of the margins at a given point in time because the company is growing so fast that they can blow out. The expense base is probably expanding as fast as or faster than the sales so the expenses will look higher than they necessarily need to be. The company needs the infrastructure to be able to support the incoming clients so it spends at what appears to be an unsustainable rate. There is a time when we should consider that a company has reached “steady state” i.e. we shouldn’t use a growth framework to evaluate it but we’ll get into that later.

That said, there are three key line items in the income statement that could be reviewed: • General and admin expense, • Selling and marketing expense, and • Research and development.

General and Admin (G&A)

Firstly, we could assume that the G&A expense will normalize at around 10% of revenues. The S&P500 companies had G&A expenses that amounted to 8% of sales, technology companies were closer to 20.1% and SAAS companies 17.6%.

As a business is growing, the G&A expense will likely be significantly higher than it would be in a steady state. This is because businesses will typically hire prior to needing the resources when they’re growing.

If the business waited until the resource was absolutely necessary, it might be too late - it would need to wait for incoming employees to serve out their notice periods, train employees before deploying, and also have sufficient space to house them. Hiring ahead of need, combined with some unnecessary growth in ancillary areas (a natural consequence of growth) will cause G&A as a percentage of sales to be higher than it would in “normal times.”

We can assume that a more mature business might have G&A expenses closer to 10% of revenues than 20%. This is consistent when we look at a larger software company like Salesforce with G&A sitting at 10% of sales.

Selling and Marketing (S&M)

Secondly, we need to make some assumptions around S&M. S&M could be broken down into two parts, 1) retention/customer success (maintenance capex), and 2) acquisition (growth capex). Next, we need to make some reasonable assumptions around where retention will fall in a steady state. We could assume that acquisition spend would be close to $0 when the market is mature. Generally, technology companies will spend a far greater proportion of sales on selling and marketing. On average, they spend 49.0% as compared to the S&P500 companies which would spend 16.9%. This could be expected, as the marginal cost of servicing a client is low, the company should spend as much as possible to grow their market share. It’s difficult to break out the growth vs maintenance components of S&M expense but we can make a more reasonable comparison when we review the Research and Development expense in a moment. We’ll cover why the difference between growth and maintenance capex is important in more detail later.

Research and Development (R&D)

Similar to S&M above, we could break S&M into two different categories, 1) growth, and 2) maintenance. S&P500 companies only spend 11.8% of their sales on R&D on average, whereas SAAS companies spend 23.3%. S&P500 companies don’t include capex in their income statement. Any expenditures on maintenance or growth capex will be reflected in the cashflow statement for traditional companies. We could potentially assume that if the company was no longer growing and expanding the code base, just maintaining it, then the R&D as a proportion of sales would likely reduce to a level closer to the more mature Old-World companies.

Maintenance vs Growth

It’s harder to break out the maintenance vs growth components of the S&M and R&D lines because of the accounting – there is no capitalized expense for software companies as there would be with purchasing new machinery, which would be classified as “growth capex.” As a result all of the expenses are passed through the income statement for technology businesses. As a proxy, if we looked at the depreciation and amortization (D&A) expense as a ratio of sales for the S&P500 companies (I know that this is a bit of a stretch but it’s a number that we can easily access), it could give us an idea of the maintenance side of the equation. However, as mentioned above, it’s completely possible that software companies require a lot more maintenance to incorporate changes in technologies.

The maintenance component of sales for Old-World businesses is 12.0%. If we combined the S&M, R&D, and D&A expense ratios, then the total S&P500 expense ratio comes in at 40.7% vs 73.0% for technology companies. Using the crude proxy, it suggests that there is ~30% that is being spent in technology companies on growth. In a steady-state, this could reduce and get closer to the Old-World businesses.

Where it exactly sits in a steady state isn’t as important as giving us a comparison to use when comparing Old-World vs New-World businesses through accounting adjustments. We can use a range in-between those numbers (40-70%) to see what outputs we’d get. We’ll work through a few examples a little later. The main point is that the accounting frameworks that we used for Old-World businesses cannot be applied to New-World businesses.

The Property Analogue

You could look at a growing software company the same way that you would look at a property company that has a large plot of land to develop. You wouldn’t expect it to build just one building and return capital when it could potentially develop 100. You’d expect the developer to finish one project and reinvest that capital into developing the next project. Only when we’re getting close to project 100, would you expect the capital to be returned to the initial investors.

Of course, this depends on the opportunity cost, if the company is able to generate a higher return on equity than an investor, you would hope that they continue to reinvest that capital. If we’re talking about publicly listed companies, then an investor could sell their holding if they have an opportunity to generate a higher return.

In Practice

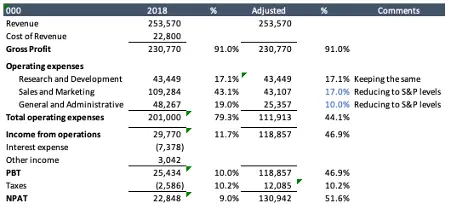

It could be useful to see what this would look like in practice with a couple of examples. Firstly, let’s look at Alteryx, a provider of a data analytics platform that “enables analysts and data scientists alike to discover, share and prep data, perform analysis - statistical, predictive, prescriptive and spatial – and deploy and manage analytic models.” Its financials look like the below:

• Gross margin: Alteryx is able to generate a 90% gross margin, which is at the top end mentioned at the beginning of the article. • Research and Development: Spend on R&D as a proportion of sales is similar to other tech names, significantly above what old-world companies spend on R&D. We’ll keep this ratio consistent to account for the maintenance capex. This will mean that the operating expense ratio will be similar to old-world. • Sales and Marketing: A large proportion of sales is being spent on sales and marketing. If this company wasn’t growing 2x year-on-year and spending as much on growth, we could assume that the S&M and G&A expenses would come in in-line with more mature businesses. • General and Administrative: G&A is ~2x S&P500 companies, this could be reduced in a steady state as noted above.

At face value, it looks like Alteryx is a US$7.2bn market cap company that’s generating US$22.9m in net profits. This would put it on a P/E >300x but doesn’t take into consideration the differences in accounting treatment of the old-world vs new-world businesses. If we make the relevant adjustments, it looks more like a business that’s trading on a 55x P/E while doubling the top line. This would translate into a .5x PEG assuming no operating leverage in the business and doesn’t look that unreasonable considering the size of the potential market and the technical challenges that it’s tackling.

When do you sell?

If we’re willing to suspend belief and accept that some adjustments to the accounting are required to get some idea of what a New-World business would look like in a steady state, then we need to have some way to appreciate when the steady state is nearing. For this purpose, I’d suggest looking at the relative changes in the Sales Efficiency defined as the Revenue Growth Rate / Sales and Marketing Expense.

As long as the company is able to generate more than $1 in marginal sales for each dollar of sales that it costs, then it’s likely still growing into an unsaturated market. If the Sales Efficiency begins to drop, then that suggests that either the proportion of sales being spent on marketing (denominator) is increasing or the rate of sales is declining (numerator), all else equal.

Conclusion

The accounting paradigm that we have historically used to evaluate businesses is sorely lacking. A number of changes to the existing accounting framework are required to make it more applicable to technology companies. This requires some assumptions to be stretched but at the same time gives us an alternative perspective. It’s inappropriate to continue to apply the same lens when the operating mechanics of businesses have changed so substantially from when the accounting rules were adopted.