Why Most VC Funds Underperform: Relative Skill and Adverse Selection

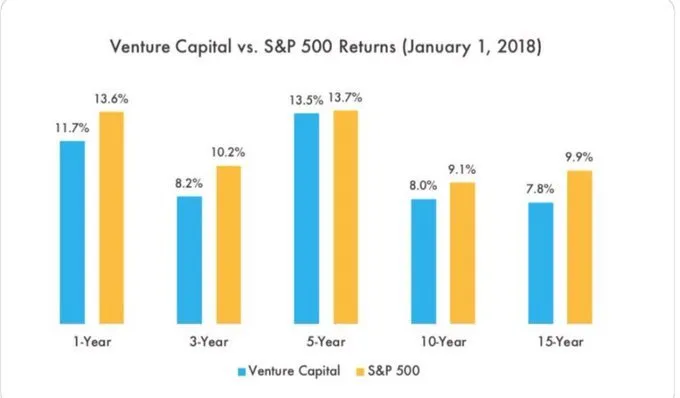

Venture as an asset class has posted some relatively poor results lately, as evidenced by the image below. Numbers would look even worse if we considered them on a risk adjusted basis considering the lock-ups and fees that are associated with venture capital. Considering the failure rates and dilution, there are a number of landmines that investors need to be able to successfully navigate to be able to create a leading venture capital fund.

There are a number of reasons why VC funds underperform the equity market. There are a number of reasons that could be used to explain this, including competition (relative vs absolute skill) and adverse selection bias. While there are other factors, let’s start with these, we can always explore further in subsequent posts.

Relative vs Absolute Skill

Michael Mauboussin discussed the relevance of relative skill as compared to absolute skill. Investment is a game of relative skill. While a manager might be a great investor, that means little when the other investors in the same asset class are better. A majority of the returns and investor funds will flow to the very best investors. Just as how there are few athletes that receive multi-million-dollar salaries, there will also be fewer investors that generate the bulk of the returns.

Further, the relatively long feedback cycle is concerning. In the hopes of buying a lottery ticket that could produce “unicorn-like” returns, people have been able to enter the space and raise funds. Despite lacking the requisite skills or resources, a new entrant could continue to operate for a number of years before there’s sufficient information to determine whether they’re actually any good as asset allocators or not. When applied to the asset class as a whole, this means that the unqualified investors will act as a drag on returns until they exit the space. This is a natural consequence of the expansionary cycle of new products — people enter, try new things, fail and then move on to the next thing.

If we were to cut-out the returns of the top 20% of firms, we’d likely see that they generated returns in excess of those demonstrated above. The remaining 80% of firms’ performance would likely be a drag on the overall numbers, which after fees produces a result below the S&P 500 (which could be replicated with liquid low-cost ETFs). While there might be certain vintages that outperform others, overall, it’s likely that if we viewed it from a full cycle, those returns would be concentrated in the top quartile of investors (venture capital has underperformed on all time periods in the above chart i.e. there aren’t any exceptional vintages in the data set but this could be strawman argument because we don’t have sufficient data).

Adverse Selection Bias

Marc Andreessen has discussed this point on Twitter a while back, to answer the question of “Why VC is dominated by a few firms?”

“Core dynamic: A few firms have positive selection on their side; the other firms have adverse selection working against them… The startup is engaged in a war for employees, customers, and future investors. Top VC brand halo helps with all three. In essence, a new startup uses its VC’s brand as a credibility bridge until the startup establishes its own brand.”

This is why it’s so hard to start a new VC firm. Why would any portfolio company want to have you as an investor if they could get a better signal by going elsewhere? Generally, what happens is a majority of firms end up investing in the second-tier opportunities in the hopes that they land a winner. As a result, those firms never get the signalling status that they strive for and they continue to get the leftovers.

Subsequently, the key question for new funds is, “How can you signal that you’re a fund that founders will want to be associated with?” This can be dealt with through a differentiated offering as well as having the ability to see things where others can’t. Neither of which is easy to do in an industry that is becoming more competitive.

Conclusion

Investing is a difficult game, absolute skill is largely irrelevant in a competitive environment. Further, first level thinkers will seldom come out with the necessary insights that produce award-winning results. There needs to be a differentiated offering as well as a different mindset if any fund manager wants to rise to the top.