Take a Chance

Every day, I’m presented with a range of new business ideas. When one of those ideas is something new, something that I hadn’t previously considered, something that makes me question my previously held beliefs, it’s exhilarating. It means that my previous paradigms are going to be shattered.

There have never been more opportunities for people to make a meaningful change in the world than we have today. However, for numerous reasons, which couldn’t be comprehensively covered in this format, there is a gap in the potential as compared to the realized innovation that is coming out of Southeast Asia. Innovation grows the pie to create more opportunities and wealth for everyone. Entrepreneurs that create opportunities and services for others shouldn’t be vilified. If the incentives are changed, it could enable entrepreneurs to take “larger” risks on what the future will look like. The benefits that would result are non-trivial and would create a snowball effect, further increasing innovation and economic opportunity for others.

To do this, we need to enable entrepreneurs to dream about what ought to be. We need to encourage investors to be bolder, enable corporates to facilitate internal innovation that puts the responsibility on individuals, and encourage the Government to adopt programs that create convex pay-offs. It is possible to close the gap between potential and realized innovation, but it requires buy-in from all stakeholders.

Think Different

Previously, I’ve written about Dee Hock and his views on innovation. He believed that people should always be thinking about ‘how things are, how they might become, and how they ought to be.’ Anyone can reflect on how things are. Investors might be inclined to think about how things might become, but only those who are willing to pick up the tools and build are willing to think about how things ought to be. In a recent essay, Paul Graham attributed “independent-mindedness” to three things: fastidiousness about the truth, resistance to being told what to think, and curiosity.

The entrepreneurs that are willing to spend significant amounts of their time and energy on non-obvious ideas are intuitively independently minded. They must be willing to explore outside of the conventional mindset to explore alternative truths. My fear is that there are opportunities being left on the table because there aren’t enough builders in Singapore that are willing to ask, “how it ought to be?”

Arguably, this is a function of the social constructs and also the relative success that Singapore has seen. In the early days of any organization, innovation reigns supreme because the upside that comes from creating value far exceeds the downside associated with failure—this is the same for countries. However, beyond a certain level of success, the seesaw sags, and process and procedure take precedence over innovation and optimization. Hastings talks about this switch in mindset from innovation to process in No Rules Rules. When preservation of the status quo and quality control are more important than innovation, then rules and regulations will govern the operations of an enterprise. This neglects to account for the convexity that’s associated with innovation in an age of apparent abundance.

What is Risk?

Depending on who you ask, they are going to define risk in different terms. Someone might think about risk in terms of opportunity cost—“What will I need to give up if I do this?” Someone who is operationally minded might think about risk in terms of the amount of time that it will take to perform an experiment or set up a process. Again, someone who is financially minded will typically define risk in terms of volatility (or the possibility of a permanent impairment of capital). The life cycle of organizations typically follows this train of risk analysis—beginning with relatively low opportunity costs to pursue outlying ideas until the risk of loss (or externally hired and financially motivated management) forces a transition to thinking in terms of financial management.

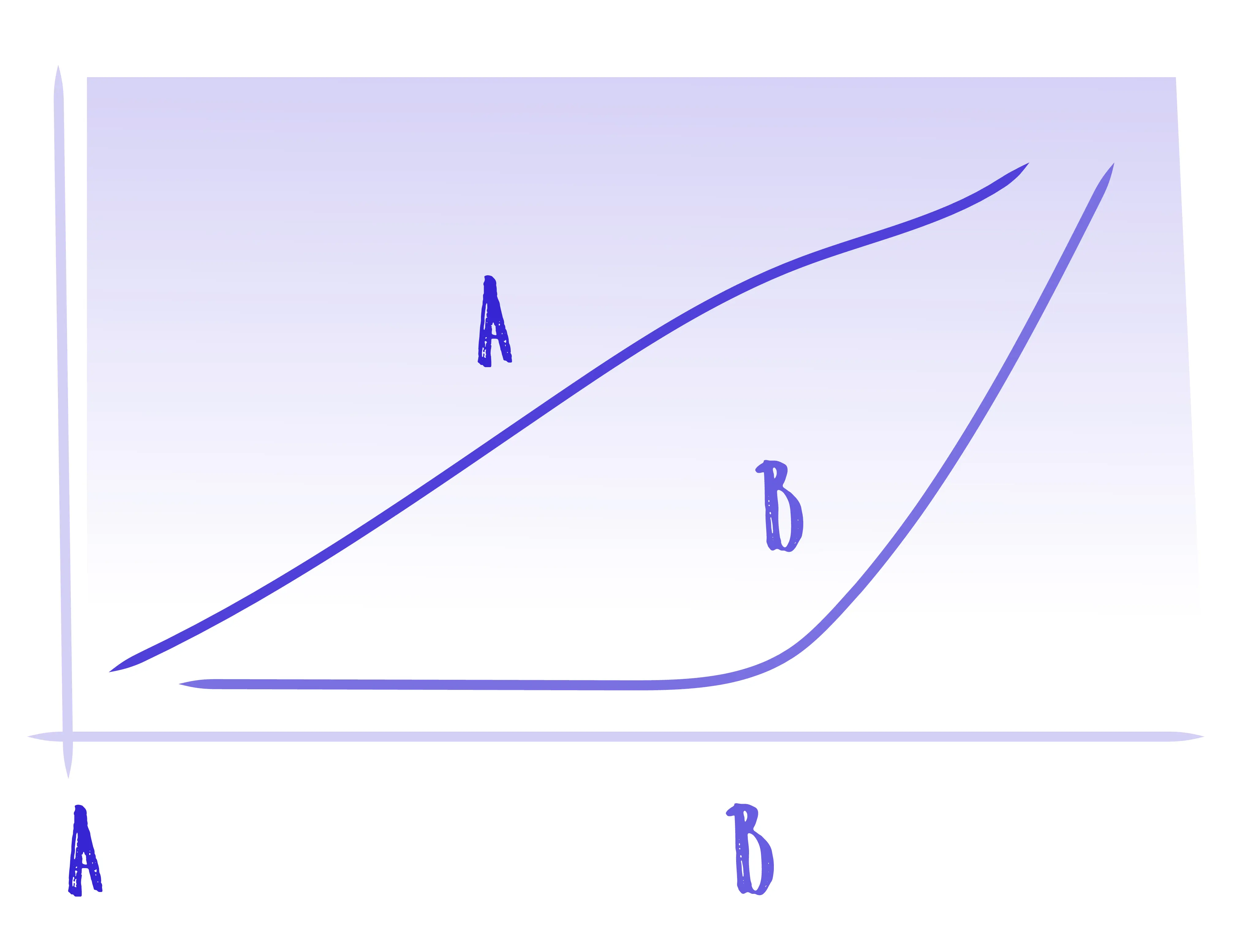

The problem with thinking in these terms is that if we’re operating at this level, we’ve typically fulfilled the lower rungs of Maslow’s hierarchy and have the ability to be more ambitious. However, the opposite is happening. Arguably, this is because risk tends to be perceived in linear terms—anything not resembling a linear trajectory is non-intuitive. However, when we’re dealing with innovation, outcomes can be structured with convex pay-offs.

Convex pay-offs will have a relatively low cost of failure but as they become successful, the pay-off from that success increases, i.e. risk is not commensurate with return—the return can far outweigh the risks. If the risk is being framed appropriately and in the right units (opportunity cost vs. financial volatility), it becomes difficult to argue against encouraging innovation at the edges. When you realize that the costs of failure are negligible compared to the potential economic opportunity that could be unleashed, it appears that there’s only one way to go.

Solutions

This issue can’t be completely attributed to the [lack of the] person in the arena. If they’re there, they’re only playing up to the crowd. A larger issue is that we’re stuck in an everlasting round of Keynes’s beauty pageant, where the investors who control the allocation of capital tend to fund things that they perceive other investors will fund. As long as everyone knows the rules and no one deviates too far from the observed norms, mediocrity can be supported. This is no excuse for ideas that are at the edge of what’s accepted—they should still be able to stand on their own two feet. However, these ideas might be forced to find audiences further afield and grow organically, failing to reach their true potential if they need to be supported by an institutionalized investor base. We need more investors in Southeast Asia who are willing to support those that are willing to be weird and tackle areas that aren’t intuitively obvious.

From a corporate perspective, we could look to the example of Lockheed’s Skunk Works, where they were able to deliver the P-80 Shooting Star, one of the first fighter jets, in 143 days. When you have people that are willing to take responsibility, operate with no ego or bureaucracy, and are encouraged to operate at the edge of what’s possible, they can deliver things that would have previously been thought impossible. Corporations could create more skunkworks—areas where employees have the ability to take responsibility for a budget and deliver marketable products on tight timelines. I’m not advocating for “pirates in the navy” but for people that can operate as guerrilla units, operating self-sufficiently from the mothership.

From the Government’s perspective, there’s potential to create an analogue to DARPA in the heart of Southeast Asia. As Ben Reinhardt points out, “DARPA is an outlier organization in the world of turning science fiction into reality. Since 1958, it has been a driving force in the creation of weather satellites, GPS, personal computers, modern robotics, the Internet, autonomous cars, and voice interfaces, to name a few.” The managers at DARPA are curious, independent thinkers, with low ego. They implement tight feedback loops and invest relatively small amounts to take “concepts from ‘disbelief’ to ‘mere doubt.’” This enables the organization to create projects that could have significant convexity in their pay-offs. The talent, intellectual property, and structures are already available here. The jump in policy that would be required is minimal.

Conclusion

We need to encourage buy-in from all the different levels of stakeholders to encourage entrepreneurs to ask “how things ought to be?” to reach our potential. This must happen at three different levels: Investor, Corporate, and Government. There are analogues (I’m aware of the paradox here) that illustrate the frameworks that could be adopted to increase innovation and economic growth. Established institutions shouldn’t be afraid of failure because the costs are low relative to the opportunity that’s being left on the table.