Getting Rekt with the Cap Stack

“Watch your step, kid (c'mon, baby baby, c'mon) Watch your step, kid (yo, you best protect ya neck)”

Wu Tang Clan – Protect ya neck

After a recent conversation with a friend and seeing some of the things that are happening in the current funding environment, I thought that it would be prudent to discuss why founders need to be mindful of how they’re structuring their funding rounds unless they want to get wrecked by their cap stack. This isn’t an area that gets a lot of attention as most founders are only trying to solve for their current funding stage and aren’t thinking about what could potentially happen further down the line. However, each stage is related and choices made early in a company’s life, could impact it later.

This is going to become more important as the air continues to deflate away from valuations and investors start to realise that there’s a difference between what a company can raise capital at in private markets and what public market investors are willing to sell it for.

An example of the differences between public and private markets can be seen in the luggage market. Samsonite has a market cap of USD4.3bn on USD3.5bn of revenue (1.2x revenue). They paid USD1.8bn for Tumi on USD550m of revenue (3.2x). LVMH bought Rimowa for USD900m when they were doing USD500m (1.8x). Away, a direct-to-consumer brand is currently running a sales process and we’ll soon find out what they’re valued at considering that their last funding round was at a USD1.6bn valuation when they had USD150m in revenue (>10x).

Generally, when investors talk about the alphabet of funding rounds e.g. Series A, B, C etc they are talking about the level of preference share. Each subsequent round would rank ahead of the previous round in the case of liquidation. Each funding round might also have liquidation preferences attached to it. A liquidation preference would mean that the investors in that round could get a multiple of their money back before the next rung down on the preference stack is paid.

As companies move through their funding life, the investors will seek more financial covenants in the form of liquidation preferences to protect their position. Series A and B investors aren’t expecting 100x returns but at a minimum they might need to generate 2-3x off each investment. To ensure that they are able to reach that level, they might put that into the funding round contractually to prevent the founders from seeking an exit at a level below their mandated targets.

Let’s put this into practice with an example:

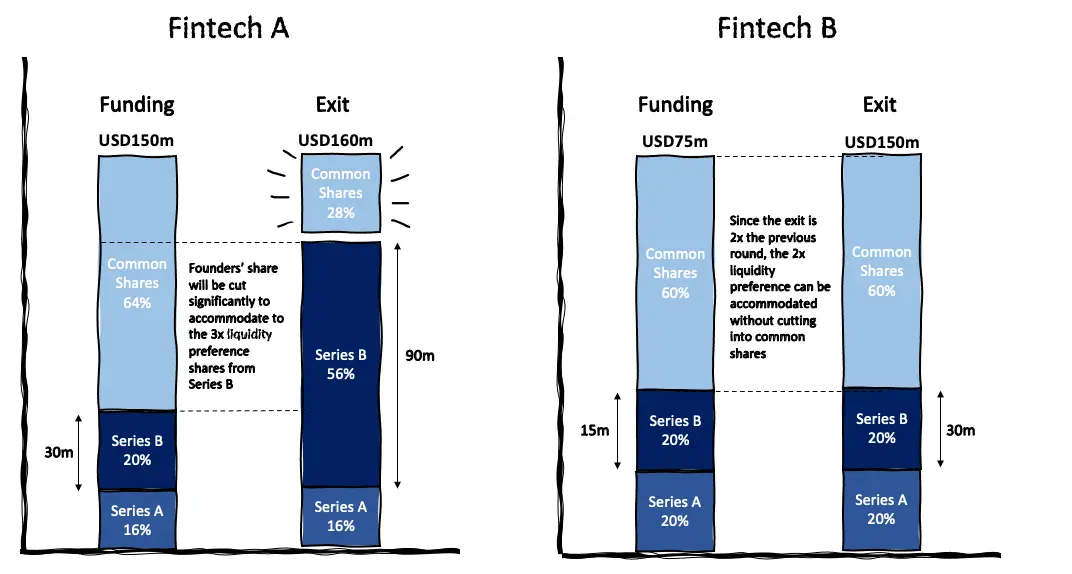

Fintech A raises USD10m in Series A funding at a USD50m post-money valuation with a 2x liquidity preference. A year later, it goes on to raise a USD30m Series B at a USD150m valuation but a 3x liquidity preference.

Fintech B raises USD5m at a USD20m post-money valuation and 1x liquidity preference (25% dilution vs the 20% dilution that Fintech A received). A year later, it goes on the raise a Series B of USD15m at a USD75m post-money valuation with a 2x liquidity preference.

Time to exit:

Fintech A is now doing USD40m in revenue and manages to sell to a strategic for 4x revenue or USD160m.

Fintech B is now doing USD25m in revenue and manages to list at 8x revenue or USD150m.

It seems like it was a better result for Fintech A, a USD160m exit vs Fintech B, who only received USD150m in proceeds from the exit (let’s assume that there’s no lock up or earn out here for illustration purposes). However, when we start to look at the fund waterfall that results from the cap stack, we get a different picture.

Fintech A’s Cap Stack

Fintech A would receive USD160m in proceeds. However, as they raised USD30m at a 3x liquidity preference (and the exit valuation is only 1.06x the previous round), the Series B investor would receive USD90m (3 x USD30m investment). The Series A investor would receive USD25.6m (USD160 x 20% x (1 – 20% dilution from the Series B). In total, the investors receive USD115m out of the USD200m or 72% of the proceeds as a result of the exit. While the founders might own 64% of the cap table but they would only receive 28% of the economics from an exit.

Fintech B’s Cap Stack

Fintech A would receive USD150m in proceeds. However, in this situation, the exit is 2x the previous post-money valuation (USD150m / USD75m) so the Series B investor is indifferent between utilising the liquidity preference or their ownership percentage. The Series B investor would receive USD30m (USD15m x 2). The Series A investor would also receive USD30m (USD150 x 25% x (1 – 20% dilution from the Series B)). In total, the investors receive USD60m out of the USD60m or 40% of the proceeds as a result of the exit. The founders still held 60% of the cap table and received 60% of the economics because they were able to achieve an exit above their liquidation preferences.

Conclusion

Obviously, we could extrapolate this out to far worse situations here where the founders and employee’s equity is effectively wiped out as a result of liquidation preferences because the multiples that public equity investors are willing to give are a far cry from those that have been seen in private markets over the last couple of years. It feels like we’re going to see a lot more of these situations over the next few years as the gap between private and public valuations see overall valuations compress. However, this is a subject for another day.

I’m always quite surprised that the liquidation preferences or structure of the cap stack isn’t something that’s disclosed to employees when they are considering renumeration offers that include ESOP packages because they can dramatically alter the subsequent pay out received by ESOP participants.

The message to founders is to protect ya neck and watch out when structuring a round.