Handicapping in SEA

When Limited Partners (who investor in funds) are picking General Partners, they need to be able to identify which investors are actually good at handicapping potential investment opportunities (and also believe that IT IS possible to identify which investors are better than average).

Considering some of the corporate governance issues that have surfaced in the last couple of years, it provides an interesting lens to evaluate the venture capitalists that have been handicapping early-stage companies. For the purposes of this article, “Investors” refers to the General Partners that are making the investment decisions on behalf of the funds that they are managing on behalf of Limited Partners.

Investors should be able to understand what’s happening in their portfolio companies from a few key data points with a reasonably high level of confidence. There will always be some issues that pop up but if they’re savvy, they will be able to use a handful of indicators that can help them to gauge the overall health of each of the portfolio companies. Any deviation in one of those indicators, will likely give reason to start digging deeper and asking more questions to understand the root of the problem.

Handicapping the handicappers

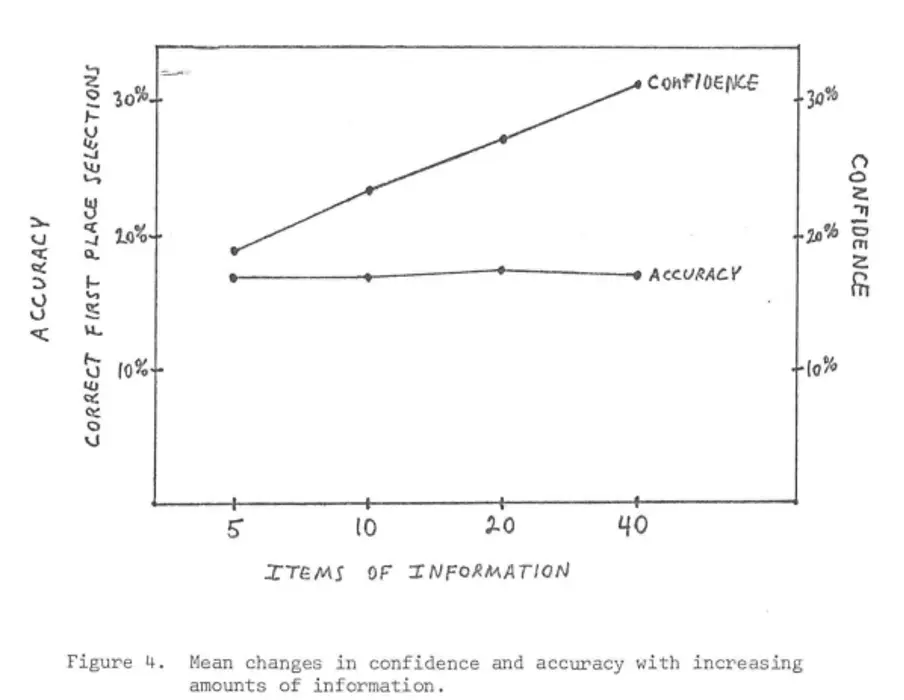

There was an interesting , where horse handicappers were given 88 variables and then asked which 5 variables they would want to use when handicapping a race. They were then asked to indicate which 10, which 20, and which 40 they would use if those statistics were available. They were then asked to gauge their confidence in the outcomes based on the amount of variables that they were able to access. The researchers plotted their confidence against their outcomes. The results show that the handicappers confidence increased when they were able to use more variables. However, the accuracy of their outcomes didn’t improve.

Investors are nothing more than handicappers, trying to make reasoned decisions based on less than perfect information. The above example is interesting when you consider the experience of some investors in the market recently. For a reasonable person, there would have been sufficient indicators in the KPIs that they would be tracking in their portfolio companies to suggest that they should have dived deeper.

Recent failures

In 2019, GoMechanic’s founder admitted to cooking the books. Amit Bhasin, the founder, was chasing growth and made some poor decisions that resulted in financial impropriety. These situations always tend to occur when markets crescendo and bad decisions can no longer be puttied over with easy capital. However, there’s something rather remarkable that ties together this situation with a few more that have appeared over the last few years and they likely could have been prevented by a savvy handicapper.

Byju suffered a fall from grace recently, after being valued at USD22bn in 2022, its largest investor has recently slashed their holding valuation to around a quarter of that. According to the BBC, former employees complained of a high-pressure sales culture and unrealistic targets. These sales tactics as well as comments from recent employees point to a company that was pushed to “grow at all costs” and disregard ethical concerns. Recently the auditors quit citing a delay in the company in submitting its financial statements, which is typically a significant red flag. Subsequently, three non-executive board members resigned from the company, another stunning red flag. The reasons that led to external red flags should have been evident to internal observers more quickly. A prudent investor would have started to dig deeper and ask more pertinent questions to understand the underlying causes sooner.

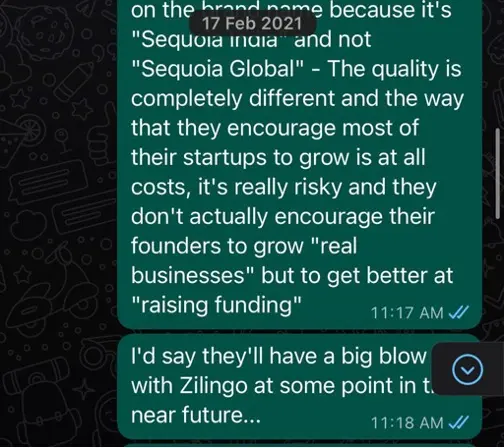

Zilingo, was another example of fraud that occurred when the founders were pushed to grow the business as ambitiously as possible. From an external perspective, there were all the signs of a fraud, I remember sending a text to a friend in February 2021 suggesting that there could potentially be a blow up with Zilingo:

One of the most glaring red flags was seeing James Perry, previously a Managing Director at Citigroup leave a 22-year career to join Zilingo as the Chief Financial Officer. These kinds of moves typically suggest that the company is looking to do an IPO in the near future. Perry lasted slightly over a year, which isn’t enough to have any stock vest but is enough time for him to get his feet under the table, realise that something is wrong, try to fix it, realise that he can’t, and then start to negotiate for his return to the mothership. Perry returned to Citigroup as a Managing Director slightly over a year after he had left.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the founders were pushed to pursue aggressive growth targets and as a result they got retailers to claim that more merchandise was moving over the platform than was really the case. The gap in revenue was plastered over with credit notes covering the missing merchandise sales. The gap between the valuation and underlying fundamentals was likely significant but a probable outcome when founders are focused on raising funds as opposed to building a business. Again, these are all things that would have been easy for a savvy handicapper to see if they were focused on the right KPIs and started to ask questions when flags were raised internally.

BharatePe founder, Ashneer Grover, and his wife had allegedly created fake companies and generated fake invoices to siphon funds out of the company. Arguably, this situation could have been more difficult for an investor to spot as investors need to rely on the information that management provides them to a degree (and the work of auditors after a certain stage). If management truly wants to go to the effort of creating fake documents and companies to misappropriate funds, this would require a different set of checks and balances on bank accounts and internal controls, which are still under the remit of a Board of Directors but can be more challenging to stop.

Trell, a social commerce platform, was put under scrutiny by the Auditor, EY India, for financial irregularities in March 2022. The company was forced to “right size” and lay off ~40% of the workforce, which amounted to 300 people being laid off. The over-hiring and financial irregularities point should have been observable to any investor director who was paying attention considering that they occurred over an extended period of time.

What’s the connecting thread?

There’s a thread that connects all these stories – All of them had Sequoia India (now Peak XV) as an influential investor. Peak XV likely oversaw and potentially had some input in all these situations.

Claiming that “It’s impossible to be over the details of all portfolio companies” is reasonable for a seed-stage investor that is trying to get a high level of diversification and not seeking board representation. However, if an investor is highly influential and typically has board representation, then you would hope that they have some level of awareness around what’s happening in their portfolio companies. If it’s beyond the level of their capabilities, then they have obviously overreached.

It's also worthwhile considering that there’s an intrinsic power imbalance in founder/investor relationships. Generally, and there are several exceptions here, founders will only pursue courses of action that their investors or board empower them to pursue. If they’re a first-time founder, they tend to err on the side of caution and ask for permission as opposed to diving over the line of acceptable behavior headfirst.

Conclusion

While it’s cute to call for the ecosystem to come together to commit to “better corporate governance,” it feels like this is a difficult ask when you’re the one that is creating the structures for corporate governance in a large proportion of the companies that you’re working with. If some of these frauds weren’t so easily visible externally, then it would be easier to excuse the board for their lack of oversight. Generally, the quality of an investment decision won’t increase with additional information. What’s really important is that the investors are looking at the right information and that they are engaged enough in the business to ask the hard questions when irregularities occur.

In the above cases, it feels like it’s far easier to blame the jockey instead of the horse considering that the issues throughout the companies were similar. It’s important that Limited Partners who are investing into funds can distinguish between the handicappers that are able to spot the appropriate risks with the relevant information and those that choose to overlook them at their own peril.